The state of data in the Judicial Sector

I originally wrote this article for the CivicDataLab blog on Medium. Follow their blogroll for other similar posts on Public Finance and Judiciary.

Judiciary, One who upholds the law, is one of the three pillars of the constitution and a really important one. The country has seen several instances when people exercised their power (granted to them by us citizens) and tried to alter the constitution according to their needs, and some of them might have lead to abolition of our fundamental rights, and it’ll only be correct to say that the judiciary was in their way, fighting till the very end to save our constitution. The times are tough ahead, with case pendency at an all time high, cases of judicial corruption making their way to our news feeds and our governments trying to use the judiciary the way they want. Barring all this, the time is also ripe for people to collaborate and brainstorm on these issues, try to be legally literate and take decisions independently instead of relying on the media for legal information. Access to justice is a fundamental right and it starts with us being curious to know more.

Past few months have been amazing for our team as we got an opportunity to work with some of the most hands-on partners in the legal space. This is our attempt to collate all that knowledge and share some insights on the data ecosystem that empowers the legal-tech community in India

- 💼 A brief on legal data systems

- 📃 An actual case document

- 👩🏽 People in Legal Tech Space

- 🗃 Improving the accessibility of Judicial data

- 🔓 Legal Tech and Open Source

- 🏛 Court cases and Data Privacy

- 🏁 Conclusion

- ※ References

A brief on legal data systems

On Ecourts:

The Indian judiciary comprises of nearly 15,000 courts situated in approximately 2,500 court complexes throughout the country [1]. There is a lot of judicial data been generated on a daily basis, but a question arises on how do we manage and make this data available to litigants, lawyers and the people of this country. To be efficient at tracking case pendency the Government of India started ecourts as an MMP (Mission Mode Project)[2] in 2007. The platform was also intended to provide transparency of information to the litigants and help judges with easy access to legal and judicial databases

Where is the data:

The ecourts website is a good entry point to start exploring judicial data. The homepage has information around metrics such as cases listed, cases pending and cases disposed across courts. The website also has links to the data portals for district courts, high courts, the supreme court and the National Judicial Data Grid or the NJDG.

On NJDG:

Setting up the National Judicial Data Grid was one of the initiatives within the ecourts project. The NJDG is developed to access aggregated case information from all District courts and few selected High courts. It’s more of a court performance monitoring tool where a user can view several important metrics and understand the performance of a court as per their pending and disposal rates. The dashboard is updated with data points from the courts on a daily basis. Though NJDG is great step towards making the information accessible and track pendency at a court level, it has its share of issues related to data completeness and our friends at Daksh wrote a detailed post on some of them.

In our research, we found that not all important queries are answered by this platform, but we appreciate the efforts by our governments as this platform is an important and welcome addition to the legal ecosystem and this takes us a step closer towards transparency. But, we still require timely advocacy efforts to make sure such tools are designed and developed as per the needs of users and not created in an isolated environment.

On Causelists:

This list is created by collating all matters issued by the Registry to be heard by the court on any day. It also contains data about the Judge and place where the matter is going to be heard.

This document is not only important for the public to track their case, but also for the researchers to conduct some important judge and pendency level analysis.

One of the major drawbacks, especially in high courts, is with the lack of standardization practices being followed while developing these reports, the formats are not fixed and most of the times these documents are scanned copies of the original paper-based (hard copies) documents, their structures across courts also vary, and these issues make them highly unsuitable for conducting any sort of analysis. A sample cause list can be downloaded here

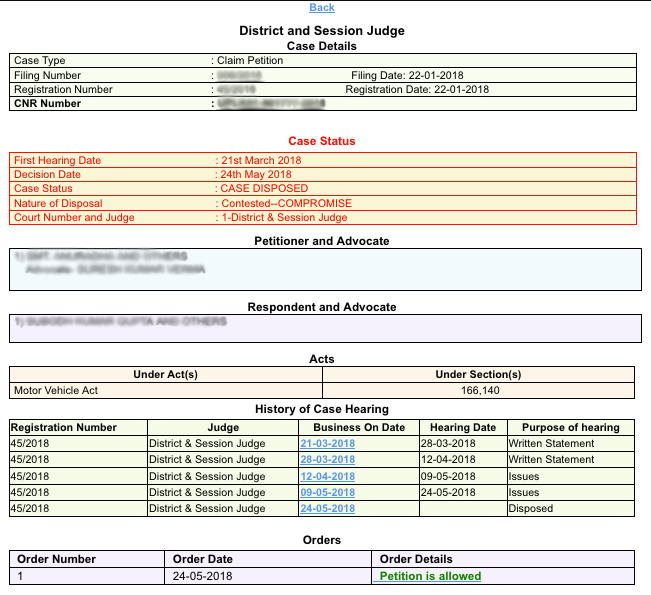

An actual case document

Accessing individual cases from court data portals:

All district (lower) courts, high courts and the supreme court have a dedicated portal for people to access their case-specific details. Every case that enters these portals is assigned a unique case number called Combined Case Number (CCN) which is made up of three components: a case type, the case number, and the year in which the case was instituted. Individual cases can be fetched from the platform through CCN or other variables such as:

- FIR(First Information Report) Number

- Party Name

- Advocate Name

- Act

- Case Type

A case is made up of a few data points:

The image below describes a case which was heard in one of the district courts. As part of the ecourts initiative, all courts are now equipped with a Case Information System (CIS), which makes it easy for the respective legal departments to store and distribute information in an organized manner. A single case comprises of more than 50 variables (data points) and information related to every hearing is recorded here (yes, its currently entered manually at periodic basis). The interim orders or final judgements passed can also be accessed from the same page.

While conducting our research, we found some issues (rather important ones) with the way information was stored that made the data processing hard and we were still not sure if we’ve written a fail-safe code.

- Data is not standardized — Case Type information is not consistent among courts. For E.g. The case code for a Bail application in Jabalpur District court will be different from Indore District Court. This issue was apparent in other fields as well. This post by Daksh describes the issue in detail

- Missing Information — The process to digitize old cases is still in progress, so there might be instances when orders/hearing information from certain cases will be missing

- Multiple CIS versions — The Case Information System (CIS) was developed in phases and we see that there are multiple versions of the software deployed across court establishments, especially high courts and district courts. If our research requires us to aggregate data from multiple courts, we might face a lot of compatibility issues among courts, this again leads to a lot of standardization errors.

- Not all high court are covered — Most of the high courts are not equipped with the latest version of the CIS and given the scale of information, this transition needs to happen as soon as possible to make it easier for researchers and policymakers and solve an important problem of data accessibility

- Bulk downloads of cases, as a feature, is not present across any version of CIS

- Case details are usually hidden behind a CAPTCHA. Though we understand the need to do so, but this makes processes complicated and creates friction for people to access the platform

As far as the CIS is concerned, we respect the work done by the people behind the software to make this information accessible and we hope that the feedback gets incorporated in the future versions. All we want is to work on and use a more robust application system, well, probably in a few years, but as early as possible.

People in Legal Tech Space

Legal Tech Collaborators

Till now we’ve observed platforms that are developed and maintained by the Government, but the article will be incomplete without mentioning some of the work done by independent collaborators which form an important part of this ecosystem and their work and ideas are consumed both by people inside the judiciary and the general public.

Indian Kanoon is democratizing access to Indian judgements through its free and user-centric search engine. The platform is free for all to search case laws, judgements and text from legal documents as the constitution of India, etc. It runs its servers mostly on free and open source software and is acting as a disruptive force to proprietary models of information and data in the legal industry.

DAKSH is a civil society organization that undertakes research and activities to promote accountability and better governance in India. They started the Rule of Law Project in 2014 in order to evaluate judicial performance and in particular, to study the problem of pendency of cases in the Indian legal system.

Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy is an independent think-tank doing legal research and assisting the government in making better laws.

Casemine, legal research and analysis platform, uses AI to unearth latent linkages between case laws, thereby making research more in-depth and comprehensive.

Internet Freedom Foundation is an Indian digital liberties organization that seeks to ensure that technology respects fundamental rights. Their goal is to ensure that Indian citizens can use the Internet with liberties guaranteed by the Constitution. This group of volunteers who worked on the SavetheInternet.in campaign post which they incorporated an organization, set up to support research regarding the online freedoms and rights of Indian citizens.

We’ve mentioned these partners specifically as some of their work is open and free to use for all. We believe that there are more partners in the space doing some important work which was evident by the 2018 Agami Summit, which awards a biennial national prize to innovations and entrepreneurial initiatives that can exponentially increase quality, effectiveness, access, and inclusion in and around law and justice. Please have a look at all the shortlisted organizations here

As we publish this blog, the Agami prize for 2018 was announced and we congratulate all the winners and participants who took part in this competition. Also, a big shout out to Agami for identifying the need and creating such a platform for creators that is only going to make this ecosystem more healthier and resilient.

Improving the accessibility of Judicial data

This discussion is an important one and we recently got an opportunity to collaborate with our partners at Vayam to conceptualize a platform that makes judicial administrative data accessible for creators (within the judicial system and outside); to design solutions that improve judicial data accessibility for citizens which further has the capability to enhance the judicial administrative efficiency and add to the transparency of information.

Yes, you must be thinking that the ecourts project is doing the same, so why do we need this additional layer. We thought about this a lot before we started our work and all stakeholders were on a consensus that ecourts is still a long way from being an open data platform and maybe it is not intended to, as well. These were some of our thoughts when we started our discussions about this separate platform:

- All data at one place — Currently all courts have their separate platforms and follow their own standards to store these datasets. To perform a comparative analysis among courts, geographies or judges is a difficult task and requires a lot of data operations.

- Adding a layer of analytics — Currently, NJDG serves as an analytics layer to ecourts, but it’s still at a nascent stage and pretty restricted in its functionality.

- Open by default — The platform should be open by default, which means no-subscriptions or logins, easy access to data, open and maintainable scripts, always room for collaboration, suggestions and improvement.

- A Co-Creation model for development — The platform will be developed for the public and should have a diverse set of people developing it. We encourage a development model that brings partners from legal, media, research, government and people from other sectors together to brainstorm collectively and have their share of responsibilities

- Building a toolbox — The platform should activate communities around it to leverage the data and build more specific solutions on top of it to improve access to citizens

We’re still scoping out our paths in the legal space and plan to share a detailed breakdown of our ideas soon. As we said above, our goal is not just to develop this platform but develop it collectively, so we will need all your important ideas and suggestions. We’ll soon release documentation on how people can contribute to these ideas. We also believe that the space and community gets stronger with more solutions getting developed and such innovations should empower each other as we’re all working towards the same goal.

Our goal is not just to develop this platform but develop it collectively

CivicDataLab collaborated with partners to develop a similar platform for the financial sector and is powered by the public finance data. The Open Budgets India Platform is now being used by researchers and policymakers throughout the country for getting access to important financial datasets with ease.

Legal Tech and Open Source

The open source community in India is still at an early stage when it comes to Legal Tech. Most platforms are proprietary and give limited access to data and tools, but the community is growing. These datasets cover all 3 V’s (Volume, Velocity and Variety) required in a strong data ecosystem and the opportunities are immense especially for folks interested in NLP and other related areas. For this class of use-cases, one of the major challenges, we believe, is the availability of legal corpora in Indic languages, which is important to understand the judgments that are not in English and this is one of the bottlenecks in increasing access to justice in a multilingual environment.

We do get some inspiration from communities outside the country who are doing a lot in legal tech.

There surely are a lot of other projects in the open which may be solving small but important issues in the legal tech space. We appreciate all the hard work done by these communities and are always inspired by them to do more.

We would like to quote some lines from the courtlistener’s FAQ section that beautifully captures the thought behind how software should be developed especially in the public and social sector spaces

But the most important distinguishing factor about this site is that it is open source and open access. Anyone can download all the source code we use to operate this site and run their own site that does exactly the same thing. And since our bulk downloads provide access to our entire collection of opinions, we hope we’ve given our effort its own life that can continue no matter what. We hope instead to be the last people who ever have to attempt to collect the entirety of United States case law. Everyone who comes after can build upon this effort.

Court cases and Data Privacy

Court judgments are public records. If a case is heard by a court of India, no one can argue that the opinion should not be published and viewable by all, unless the court itself expressly says it cannot be published or a law says it cannot be. Courts today are publishing their judgments and orders on the Internet. Section 52(1)(q)(iv) of the Copyright Act states that the publication of court judgments does not constitute an infringement of Copyright.

Please check out this post by IndianKanoon for an in-depth look at the topic

Conclusion

This is a long read, but we hope that it manages to demystify legal-tech a bit. As we’ve mentioned at the start, Judiciary is an important part of who we are and what we represent. As citizens, let’s try our best and question the ones in power, have meaningful debates and try our best to collaborate and work towards some of these challenges. Let’s try and be legally literate and defend our rights when required.